Looking at contemporary posters, one may have the impression that they do not possess any artistic value and their only purpose is to advertise and inform the customer of the product. However, when looking at the condition of the Polish poster in the past, it appears that the situation was not always that mediocre. What becomes immediately apparent is the stark contrast between Polish posters from the 1960s and the commercial character of posters today. It appears that nowadays there is no place for innovativeness, individualism and ingenuity. What is representative of the Polish School of Posters is its complexity, its emphasis on artistic forms and the unity of form and text which makes it so different from the strictly pragmatic and commercial character of Western designs.

In order to understand the quintessence of the Polish poster and the way visual arts had been evolving in Poland, one should first know about some of the political and historical aspects of the 18th and 19th century. At the end of the 18th century, Poland disappeared from both the political and geographical map as it was split between three empires that ruled Europe at the time: Russia, Prussia and Austria. The national identity of the Polish people suffered from restrictions of various intensity and character, depending on the empire that ruled a particular part of Poland. In order to express their discontent with those limitations, the Polish people organized numerous rebellions against their persecutors. One of the biggest and most violent ones was the January Uprising in 1963 organized on the territory controlled by the Russian Tsar. The insurrection became a romantic and drastic step that eventually worsened the attitude of the Russian oppressor towards Poland. In consequence, further restrictions were introduced which had a severe impact on the cultural and national freedoms of the Polish people.

The territory of the officially nonexistent Poland controlled by the Austria-Hungary Empire was called Galicia and its capital was Cracow. In view of the situation that occurred in Warsaw, the local cultural Polish leaders abandoned the heroic approach, turning instead to positivistic pragmatism. They rejected drastic, patriotic rebellions and preferred to work on social fundamentals, gradually improving people’s living conditions. By remaining relatively 'loyal’ to the Austrian government, the Polish people in Galicia gained some limited rights and liberties (for example representation in the Parliament and relative cultural freedom). Therefore, Cracow became the center of Polish culture and had enormous impact on the young Polish artists of that time. They were the first to object to Positivism and refer to the roots of Romanticism. That movement appeared in the late 19th century and became widely known as Secession. The Polish people also called it 'Młoda Polska’ (’Young Poland’) and that was the time when such renowned Polish artists as Józef Mehoffer, Stanisław Wyspiański, Karol Frycz, Kazimierz Sichulski and Wojciech Weiss were active. They emerged as the elite of the Polish artistic scene largely influenced by the manifesto of Artur Górski published in 'Życie’ (Life) in 1898. The term 'Young Poland’ was first used in the manifesto and it became the credo of the Polish Applied Art Society (an influential artistic organization active in Galicia). 'Young Poland’ was a patriotic and secessionist movement, particularly important for the persecuted society as it related to the revival of Polish individualism and the rejection of the positivistic doctrine. There were analogical movements abroad, like 'Young Germany’ or 'Young Belgium’. For Poland, the turning point in those aspirations was the International Exhibition of the Poster organized in Cracow in 1898. Jan Wdowiszewski, the director of the Technology and Industry Museum in Cracow, headed the Exhibition and a great advocate of Polish culture and freedom. The following years were a time of rapid development of the Polish poster, which was tragically interrupted by the First World War. After fours year of turmoil brought by WWI, another period of prosperity for the Polish poster began in 1918 when Poland regained its long-desired independence. Having unified its territories, the country was experiencing extensive industrial and commercial development. Because of the need for promotion, the role of advertisement became extremely important in the lives of ordinary people, giving the poster large space for development.

Another factor that contributed to the extensive demand for posters was the fact that Poland (as a newly unified country) became a tourist destination. The poster was a perfect tool for encouraging not only foreigners, but also people from various regions of Poland to visit places located on the territory previously unavailable to them. The most significant example of that tendency was the series of tourist posters by Stefan Norblin. His works featured vivid colors and conveyed clear messages. The series covered such works as: 'Poland’ (1925), 'Gdynia, New Baltic Harbour’ (1925), 'Lvov’ (1925), 'Vilnius’ (1928).

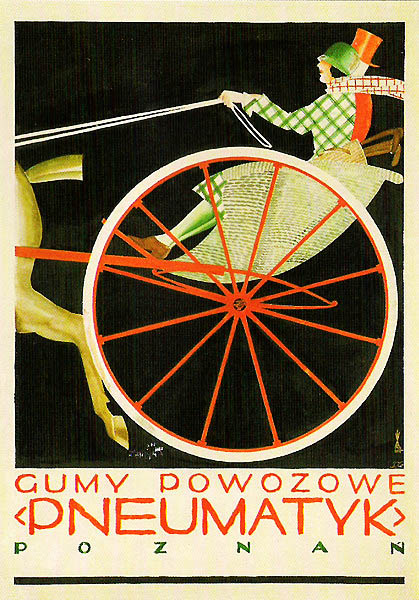

Although the art of the poster in Poland was already highly developed at that time, its true bloom was still about to come. The most distinguishable poster designers in the period between the wars were Tadeusz Gronowski, also called the 'Father of the Polish Poster’. He was the first Polish artist who focused mainly on designing posters. While studying at the University of Warsaw, he was a member of a group of students who rejected the artistic tendencies of the past. They stopped imitating natural forms and turned to cubism with its geometry and the innovative artistic techniques available at the time. Tadeusz Gronowski’s works became the milestone for what was later called the 'Polish School of Posters’. Although Gronowski was a widely educated painter, unlike Stefan Norblin, he did not make use of painting forms and techniques in his posters. Instead, he aimed at creating something new. It is thanks to him that cubism became the trademark of the Polish poster for nearly two decades. Other notable names related to the poster of that time were Edmund Bartłomiejczyk, Tadeusz Trzepkowski and Józef Mehoffer.

'Tier’, 1923

The economic prosperity, which contributed to the success of the poster between the wars, has its reflection in the establishment of the LOT Polish Airlines in 1929. Because flights were still unpopular at the time and people feared to travel by planes, LOT cooperated with artists like Gronowski to attract customers. The period of that affluence was finally interrupted by the onset of the Second World War. Like other forms of artistic and social activities, the war hampered the initiatives of poster designers.

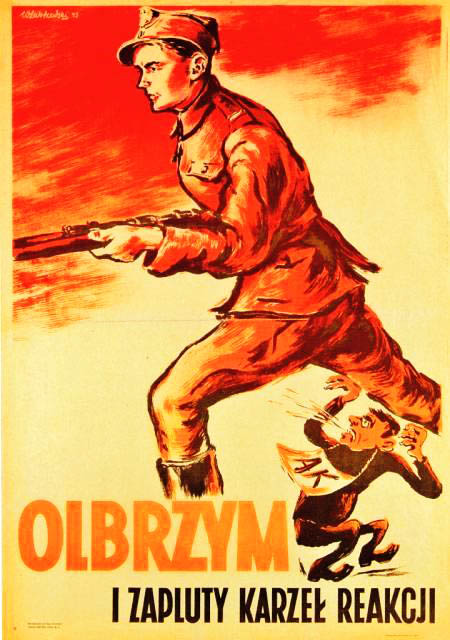

After the Nazi Germany was defeated in 1945, Poland was transferred into the hands of another totalitarian regime. Against the will of the 'liberated’ Polish population, the Communists ruled the country. They found that posters were a very useful tool for controlling and manipulating the society in order to remain in power. For that purpose, the Propaganda Poster Studio was established in Lublin, a city on the territory of contemporary Eastern Poland. The Polish United Workers’ Party, strongly influenced by the Soviet Union, strictly controlled the actions of the Polish poster artists. The most important representative of the Studio was its head Włodzimierz Zakrzewski, a gifted painter educated in Moscow. He was also a Communist activist entirely devoted to the destructive socialist ideology. He based the style of his posters on the principles and forms that he learned in Moscow. Given some propaganda slogans, he was instructed to adjust the graphic forms to the ideological purposes of the system. For the first time in the history of the Polish poster, it became institutionalized.

'The Giant and the Disgusting

Reactionary Dwarf’ (1946)

The 'Reactionary dwarf’ poster features a soldier of the Home Army of Poland (Armia Krajowa) that fought hand in hand with the Allied Forces. Despite their merits, the Communist government persecuted the activists of the Home Army after the war as they were perceived as the enemies of the system. The Communist government feared that the soldiers might pose a threat to the socialist rule. Posters constantly remain in touch with the viewer; therefore, they perfectly reflect the social and political atmosphere of the time in which they are created. As the early years of Communism in Poland were marked by restrictions and persecution, many young and accomplished artists opted for the cooperation with the regime as they often had no reasonable choice. Otherwise, they would have been forced to work in the artistic underground without any opportunities to get across to the public. Propaganda posters of that time depicted smiling workers and farmers praising the merits of the Communist system. One of the most famous posters of that time presented a woman energetically performing her duties of a tractor driver. Posters also featured proud and strong soldiers who bravely and successfully fought against the enemy in the service of Communism.

In the late 1950s, when the Communists had relaxed their approach, Poland gained relative autonomy. That marked the beginning of the period of the golden age of the Polish poster. The artists were still controlled by the state via such institutions as Film Polski (Polish Movie) and Centrala Wynajmu Filmów (Movie Rental Central); nonetheless, the poster remained the only unrestricted form of creative and expression widely available to the public. As a result, posters became associated with artistic freedom. There are several factors that contributed to the development of the distinguishable Polish poster style.

'Alban Berg – Wozzeck’ (1964)

Firstly, Polish artists obtained wider opportunities to travel abroad and establish relationships with Western artists. Secondly, due to the fact that Communism strongly opposed the capitalist models, commercial premises did not drive artists during the process of creation and they could focus solely on the artistic aspect of their works. Unlike the Western tendencies, the Polish poster became one of the fine arts: 'The artists requested and received complete artistic freedom and created powerful imagery inspired by the movies without actually showing them: no star headshots, no movie stills, no necessary direct connection to the title’ (source: Smashing Magazine)

The very term 'Polish School of Posters’ was officially coined in 1960 by Jan Lenica in his article published in a Swiss magazine titled 'Graphis’. Jan Lenica was not only a critic, but also an active artist in the field of the Polish poster. His works were full of expression, however, one may also find there sarcasm and satire. The form of his designs was often revolutionary compared to the condition of posters at the time. He developed his own writing style which, despite many changes and improvements, remained his unique trademark. In the 1960s, he started applying the cutout style in his posters, which became another characteristic feature of his designs. He was the author of over 200 movie and theatre posters and one of his most renowned works was the poster for 'Wozzeck’ opera by Alban Berg. His designs were full of absurd and irony that he treated as the means to create a completely new, often grotesque reality.

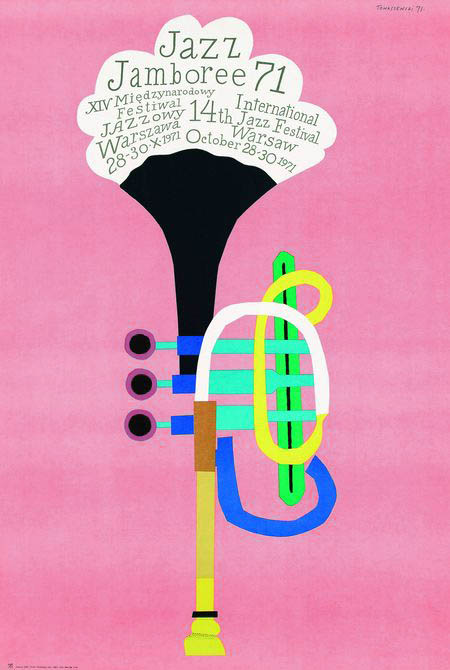

Contrary to the consumerist shallowness of the Western poster, the Polish artists conveyed a sense of sophistication and refined culture in their works. One of the most renowned designers of Polish posters at the time was Henryk Tomaszewski. He never conformed to the pressure of the Communist Party, remaining artistically independent in that respect. His posters were deliberately exaggerated and satirical and the artist frequently made use photographic montages, distorted perspectives and minimalist compositions.

'Jazz Jamboree 71′, 1971

Among the artists who contributed significantly towards the maturity of the Polish poster one may also find Maciej Urbaniec. Educated in Tomaszewski’s studio at the Fine Arts Academy in Warsaw, he received worldwide recognition. Except for numerous honors in Poland, Urbaniec was awarded the medal at the International Biennale of Graphic Art in Bern and the 1st prize at the International Editorial Art Exhibition in Leipzig. What was characteristic of his works was their humorous character, simple and expressive messages and symbolism. He closely cooperated with the State Publishing Institute (a prestigious publishing agency in Poland) as a designer of book covers and posters.

When speaking about the Polish School of Posters, we should not forget about one of its founders, namely Jan Młodożeniec. He cooperated with the Movie Rental Center as well as numerous publishing houses and theatres. He received many prestigious awards, e.g.: the medal at the International Biennale of the Poster in Warsaw 1980 as well as the prize at the Biennale of the Poster in Lahti, Finland 1983. He developed his own distinctive style that he called the 'personality poster’. His works may be seen in Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, Kunstbibliothek in Berlin, Biblioteque Forney and Musee d’Arts Decoratifs in Paris, Museum of Modern Art in New York and numerous private collections in Poland and abroad.

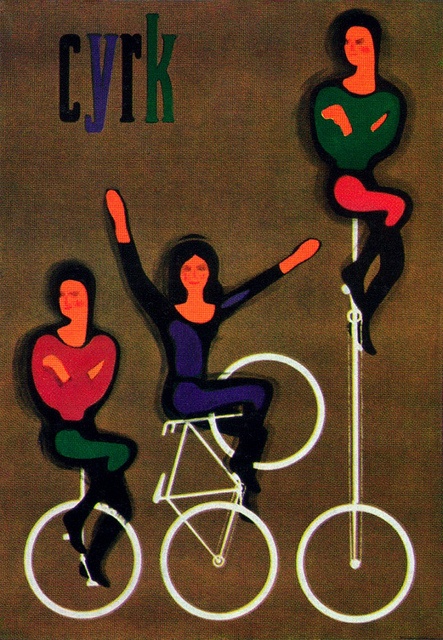

One of the most recognizable trademarks of the Polish School of Posters were CIRCUS posters which were created in Poland until 1989. It was an initiative by Zjednoczone Przedsiębiorstwo Rozrywki (the United Entertainment Enterprise) that aimed at promoting the refined character of the circus poster and changing the very image of the circus. Circus posters featured clowns, jugglers and animals (typical circus imagery); however, they were full of hidden metaphors, allusions, symbols and artistic devices. Other renowned names that strongly influenced the Polish School of Posters were Roman Cieślewicz, Witold Gorka, Jerzy Flisak, Eryk Lipiński, Marek Mosiński, Waldemar Świerzy and many others.

The Polish School of Posters was a movement that constantly triggered emotions and controversies. In 1963, the 'Graphis’ magazine, which had been following the development of the School since its inception, went further and concluded that the total absence of commercial and pragmatic aspects in the Polish poster as well as its extremely individualistic character led to a situation in which the poster lost its roots and original function. One may also argue that the Polish poster did not have its specified, uniform character; however, some features make it extremely unique and these are: allusion, symbolism, individualism and the ability to use every subject to present issues concerning Poland. The Polish School of Posters flourished in the mid 1960s; unfortunately, the next decade marked the beginning of its decline. Its final death came along with the end of Communism era in Poland in 1989 and the arrival of the free market. Poland started absorbing Western tendencies and patterns, which deprived it of its originality and distinctiveness.

At present, the art of posters faces numerous difficulties. Billboards are created overnight based on television snapshots. Young graphic designers cannot cope with the aggressive consumer market. The availability of designing tools and opportunities allow unskilled designers or even amateurs to offer their services on the market. The separation of the artistic design seems to be a natural and unavoidable process. Therefore, certain questions come to mind when thinking of the contemporary poster: Is there any point in creating contemporary artistic posters? Should we create artistic posters only to display them in galleries? Will the traditional and artistic poster withhold the pace of that lifestyle that people run today?

Undoubtedly, the poster today will not function in the same form as it did in its golden age as the pace of life, huge advertisements and commercialization are unavoidable. However, that is only the mainstream aspect of ordinary people’s lives. On one hand, new technologies allow dilettantes and amateurs to influence the character of posters; one the other hand, they also ensure versatility that leads to something new. Because new technological opportunities, like the Internet, provide free access to various forms of creation, they may contribute to the rejection of mainstream trends and economical aspects analogical to the situation that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. Therefore, I believe that the poster is only waiting for its rebirth.

Author: Grzegorz Zawora